Look at the children’s section of a bookshop anywhere else in the world and you’ll find a whole range of books by British and American writers. Children in France and Germany and Sweden have heard of Roald Dahl and Michelle Paver and Stephanie Mayer. Children everywhere have heard of JK Rowling.

But how many British children could name a writer who’s published in translation in Britain? How many British parents? I think I know a fair amount about children’s books, but only a handful of writers who don’t write first in English spring to mind immediately. True, if you gave me a list, I’d go ‘oh, of course, I forgot about him or her’ to a couple of handfuls more, but still, it’s not many.Of course it’s not surprising that British children’s books are famous throughout the world. We in Britain have now and have had in the past an unbelievable wealth of extraordinarily talented children’s writers. And, as explained to David Almond in a fascinating BBC Radio 4 programme last year, the British publishing industry model is based on the principle of selling British books into foreign markets, a principle which isn’t so entrenched among foreign publishers.

But what are we missing? What fabulous writers will we never come across because they write in languages other than English and no one’s translated them? And while we celebrate and seek out diversity in children’s books, shouldn’t we include the diversity brought by exposure to other nations and cultures?

I’m thrilled to discover that there is one publisher, Pushkin Press http://pushkinchildrens.com who is dedicated to bringing the very best children’s books in translation to Britain. And once you’ve read all they have to offer, here are a few of my favourites.

FANTASTIC WRITERS FROM OTHER COUNTRIES

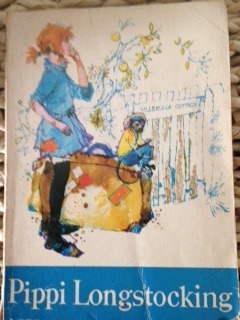

Astrid Lindgren

Astrid LindgrenOf course you’ve heard of Pippi Longstocking, the strongest girl in the world, who lives by herself in a tumbledown house, with a monkey and a horse. You’ve heard of her … but have you read the books?

Goscinny and Uderzo

Asterix the Gaul and his companions pit their wits against

the might of the Roman Empire (with the aid of their magic potion). Asterix’s

flawless translators, Anthea Bell and Derek Hockridge, demonstrate the difference really good translation makes.

Asterix the Gaul and his companions pit their wits against

the might of the Roman Empire (with the aid of their magic potion). Asterix’s

flawless translators, Anthea Bell and Derek Hockridge, demonstrate the difference really good translation makes. Edith Unnerstad

Edith UnnerstadOh how I loved The Saucepan Journey, Little O and The Urchin, funny stories about the Swedish Pip-Larsson family. Out of print in English, but look out for them in secondhand shops.

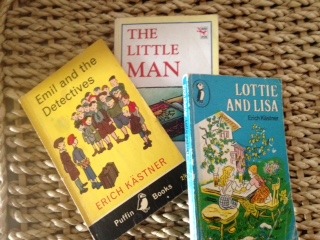

Erich Kästner

My favourite was Lottie and Lisa (republished as The Parent Trap by Pushkin Press in a translation by Anthea Bell), but try Emil and the Detectives and The Little Man too.

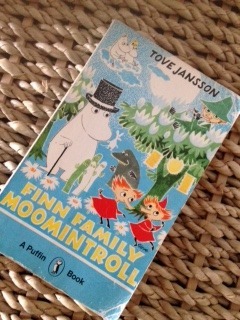

Tove Jansson

There is nothing in the world like the Moomins.

Michael Ende

Michael EndeBastian falls from his unsatisfactory real life into the enchanted world of The Neverending Story, which he alone can save from destruction.

Cornelia Funke

Cornelia FunkeIn her Inkheart trilogy, book worlds and characters collide with the real world. Seek out her other books too, Dragon Rider, Igraine the Brave and the Mirrorworld books.

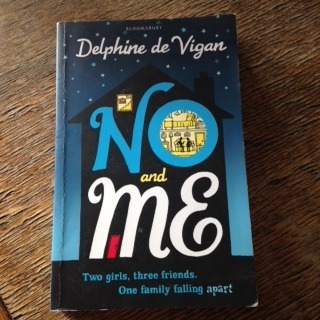

Delphine de Vigan

No and Me is the story of a girl who decides to interview a homeless teenager in Paris and ends up enmeshed in her life. It’s one of the few YA translations I’ve come across.

I’d love to hear about your favourites. I can’t help wondering if maybe there’s more of this stuff about and I’m just being blinkered.